Dear Amy Cooper

May 26, 2020

Dear Amy Cooper,

I write this letter to you, Amy Cooper, as a way of writing a letter to myself and my white liberal friends who say we care deeply about racial injustice – but don’t want to admit we are anything like you.

First of all: Your apology needs to be the beginning, not the end, of this story. Your apology needs to take root in your soul, not so that you can make it about you and feel like a terrible person -- that is going to get us nowhere -- but so that you can understand that we don't only apologize when we've been exposed and embarrassed. It doesn't undo anything.

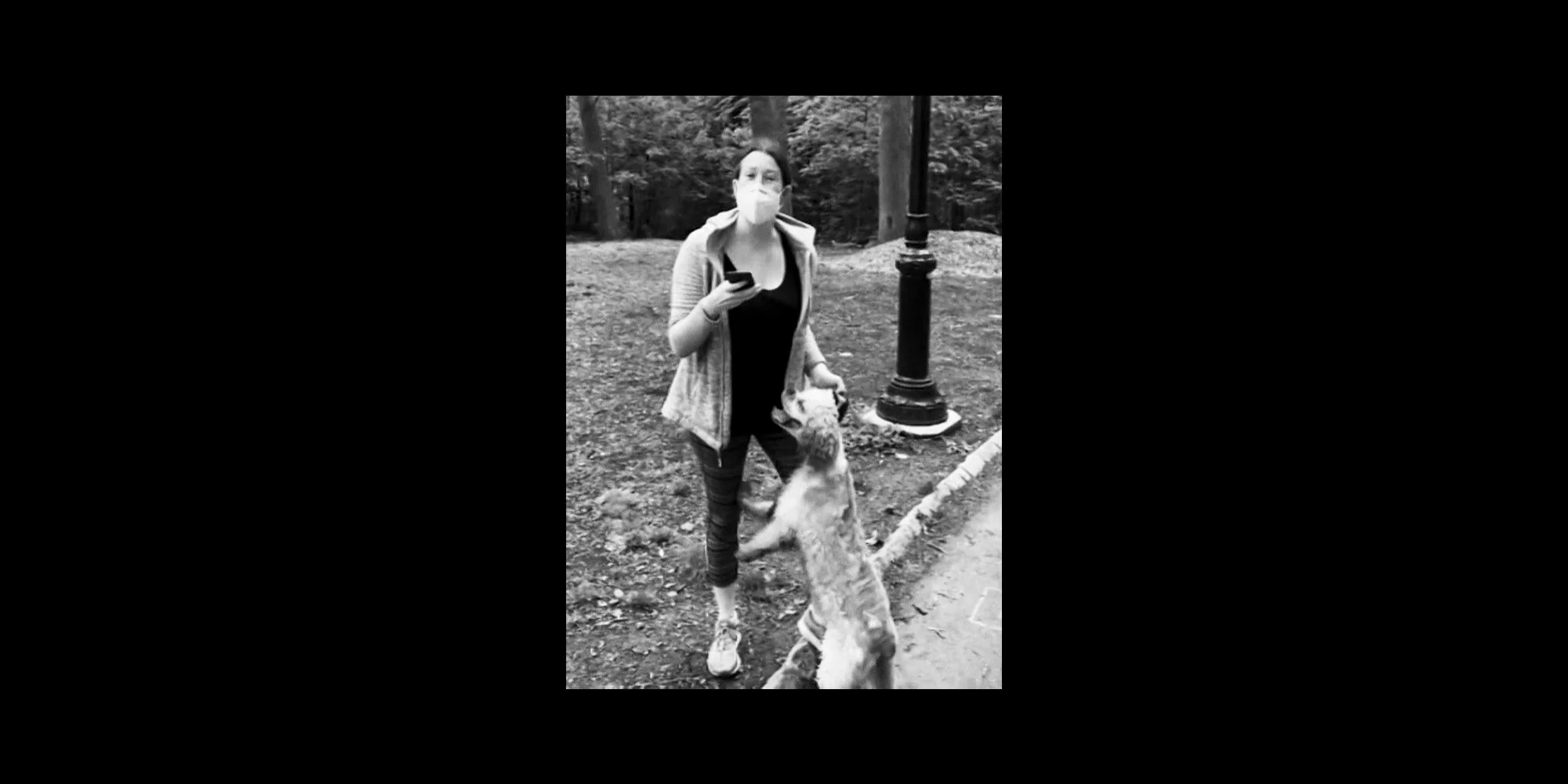

Your actions in the park were violent. That's right, violent. I would say "careless," but that would apply more if you had left your purse sitting in the middle of the aisle on a plane and someone accidentally tripped over it. No, calling the police and reporting "an African-American man" who was enjoying nature and asked you to leash you dog -- in a part of the park where leashes are required -- is an act of violence. It is also illegal.

This is how people of color die in America every day of every year, while going about their everyday business doing everyday things. Have you ever, even one single time, in your own life paused to consider how stressful and exhausting that must be?

You said you were "just scared." Do you know how many Black men have been arrested or murdered because a white woman said she was "just scared”? There are rules in our country that apply to everyone, but you chose to break them by letting your dog off-leash in a part of the park where leashes are required. The man who confronted you had every right to do so and did so without the least suggestion of harm. Is this how you respond to being told you are not exempt from the rules?

Here is the thing: You don't get to place a phone call to the police to report "there's an African American man threatening my life" and then then the next day add, ""I'm not a racist. I did not mean to harm that man in any way." If you were scared, which is dubious at best, it was YOUR job to a) go where the rules of the park clearly dictated you could have your dog off-leash or b) apologize to the man and put your dog on its leash or c) leave.

Better yet, choose option c with the additional work of going home, getting out your journal, and writing about why you made that call. What stories and images of African-American men have you seen and heard that have caused you to believe that someone birding in the park would pose any kind of threat to you? What would it be like for you to sit with that fear, to get to know its origins, and to commit to being honest about the ways growing up white in a racist country have shaped your beliefs and behaviors -- then changing them and rolling your sleeves up to change this?

Asking these questions is not just your job. It is the job of all of us with white privilege who believe we aren’t racist. Who are horrified at the suggestion that we are racist, even when we have just endangered someone’s life.

I myself live with the unearned freedom of having white skin in America. I love birds. I love parks and running and solitude and gathering with friends when it's not a pandemic and raising my kids and walking my dog and going for a long drive with my wife. In other words, I love doing all of the normal things that quickly become matters of life and death for Black people, often because of phone calls just like the one you made yesterday.

It is naive to wish you would make this a turning point in your life. It is more likely that you will make it all about you and your shame, or you and your fear, or you and how unfair it all was. Because that is what we, as white women, do when we are “caught” being racist. We defend or cower or deflect or put ourselves at the center of the conversation instead of realizing that what we need to be talking about is where we learned in the first place that Black people should be feared, where we learned in the first place that we could skirt the rules, and where we learned in the first place that the system will protect us every single time, no matter how seemingly minor or outrageously overt our racist actions.

White outrage on social media in an echo chamber doesn't change anything. In fact, I hesitated to write this at all for that reason. But white silence is just as deadly as the phone call you made could have been for Christian Cooper. An apology after the fact is not enough. As white women who have so much power in this country – yes, even under Trump – we have to keep challenging each other to do more than intermittent outrage. We can’t settle for sadness or wringing our hands about not knowing what to do.

We have to be talking to each other about what we can DO and then DOING IT. The “it” will never be enough, but that does not mean we can allow ourselves to fall into the illusion that racism is separate from us, something that evil white women with cell phones perpetuate but surely not US. No, we must do the dual work of looking within at where we have internalized bias, unfounded fears, and even epigenetic beliefs about Blackness – while also committing to taking action on a continuous basis. The internal work will not be flashy or even visible; the external work will be frustrating or seem like too little.

Too many people have died and continue to die because of us not doing this work. It has to stop, and it won't if you – if we – keep calling the police instead of looking in a mirror and holding that mirror up to each other until a day comes when it’s no longer necessary to do so. That day may not come in your lifetime, Amy, or mine, but I’ll be damned if it’s not on us to keep working towards it.

There is not a single one of us who isn’t responsible for doing our part. I cringe to think we are anything alike, Amy Cooper. But the truth is, as long as white women like myself insist that we are nothing like you, we will distance ourselves from the work that so desperately needs to be done.

Updated to add: I wrote this letter to you before members of the Minneapolis police department murdered George Floyd, not 24 hours after you made that phone call.

As Ibram X. Kendi wrote, "We should be drawing a straight line of racist terror from #AmyCooper to this Minneapolis cop. Too often, she is the beginning. He is the end."

Sincerely,

Jena Schwartz